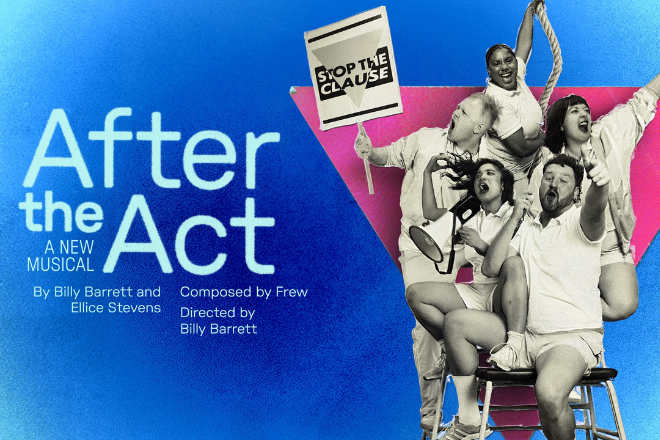

If I had a pound for every time a friend has asked me “have you seen After The Act at the Royal Court?” this week, I would have… around five pounds (but you know what I mean).

I quite enjoy be able to respond by saying “oh, I saw After The Act at the Albany in Deptford last year”.

I was so happy to hear that After The Act had been picked up by somewhere as prestigious at the Royal Court Theatre as it is an incredibly moving story, that is sadly just as relevant today as it was forty years ago.

What was Section 28?

Section 28, was a 1988 Local Government Act in the UK, which prohibited local authorities from “promoting homosexuality” or teaching about it in a positive light in schools. This legislation was in place until 2003, impacting schools, local councils, and LGBTQ+ people.

I saw After The Act last year with some friends who are a few years older than me. What was really interesting, was the conversations we had during the interval and after the show about our experiences of living through the years of Margaret Thatcher‘s Section 28.

I was six years old in 1988 when this legislation came in to place and so almost all of my school years were affected by this law, whereas my friends were on the picket lines, protesting for the law to be overturned. Listening to stories and hearing how this transcended through generations was quite fascinating.

Growing up, Gay, and not knowing what that meant (because no one was allowed to talk about it), led me (where I imagine it led many confused young people) to take to the fairly new invention of ‘the internet’, to try to understand my feelings and connect with ‘other people like me’.

Of course now, if you mention talking to random strangers in internet chat rooms, you would know to steer clear. But in the 90’s, when Section 28 meant that young gay people felt alienated and confused about themselves, when a man (twice your age) offers to ‘meet up’ with you to ‘teach you what it means to be gay’ – you jump at the chance. That’s what happened to me anyway and I’ll leave it to your imagination what lessons he taught me before passing me around to other much older men as part of my ‘education’.

After The Act is a real life account of what those years were like for many people and demonstrates the eerie similarities we see now with transgender people, all around the world. It is an urgent reminder that the fight for LGBTQIA+ rights is not over and we can’t rest on our laurels hoping it will all just disappear. We have to continue to fight.

I would love to see After The Act transfer in to the West End for a short run after it ends at the Royal Court Theatre because it truly is a piece of theatre that deserves to be seen.

Here is an interview with the creators of After The Act.

Tell us what After the Act is about?

Ellice: After the Act is a verbatim musical about Section 28, the legislation which meant local authorities couldn’t ‘promote’ homosexuality, which was in law from 1988-2003. It sets out to tell the story of this one piece of legislation, from the build-up that saw the law being passed through government to the legacy it left behind. It uses first-hand

testimonies to paint portraits of the people who were most affected by it – whether that’s teachers teaching under it, students at school during the time it was in law or the activists that fought against it. It also centres the parliamentary debates and the way it was discussed in the media to show the difference between how it was being discussed in these very public forums vs the reality of how it was affecting people on a personal level.

What made you want to tell the story of Section 28 now, and as a musical?

Billy: I remember discovering a few years ago that I had been at school under Section 28. We think of it as a relic of the 1980’s. But in fact it wasn’t repealed in England until 2003 – my first year of secondary school. As I’ve since learned, although it was then taken off the statute books, in practice it cast a really long shadow over education.

Teachers remained afraid to confront LGBT topics in schools for a very long time. This explained a huge amount about the ways that people of different sexualities or gender identities were talked about – or rather weren’t talked about – at my school.

When I realised the 20th anniversary of its repeal was coming up in 2023, I suggested to my co-writer Ellice and our musical collaborator Frew that we try and tell the story of

the legislation. The anniversary was an opportunity to have a look at how much, or little, has changed in the intervening years. We were excited by the possibility of using music

to access the world of 1980’s Britain. And by the challenge of combining that with Breach’s usual investigative, research-led approach.

Can you tell us a bit about how you began the creative process?

E: We began at various archives in London, looking through news media archives and seeing the headlines from the time that labelled LGBT people as “looney lezzies” and other derogatory terms. We mined those archives to try to get a real sense of how the debate of LGBT inclusion in education was being framed, and how queer people were generally being talked about in these public arenas. We also began looking through the Hansard archives and were really shocked by the language politicians were using to talk about these communities.

Then, we did a call out to speak to teachers, students, activists or anyone who wanted to talk to us about their experience of Section 28. We conducted about 30 interviews with people and that felt like such an immense privilege that people wanted to share their stories with us. It felt like for a lot of people this was the first time they’d ever really spoken about it.

Tell us about collecting the real, verbatim accounts used?

B: Oddly enough, the very first person that we interviewed for the show was Sir Ian McKellen. He was a really key figure in the fight against Section 28 and the establishment of what became Stonewall. They are the UK’s leading LGBT campaigning organisation. He was so generous with his time. And he shared some fascinating memories with us, including of his own public coming out on a BBC radio debate about Section 28. His enormous personal archive of campaign posters, flyers, meeting minutes and correspondence led us to discover Before the Act. This was a fundraising variety evening he had a hand in putting together before Section 28 passed in 1988. It featured a whole host of brilliant actors performing songs and scenes by queer writers. That gave us our title. It inspired us with the idea of blending songs and scenes – though in a very different way – to tell the less well-known stories of people around the country impacted by the legislation.

Can you tell us about the characters in the play?

E: That’s a hard question as there’s so much multi-roling, but there are some characters which have come from the interviews we conducted that make the spine of the show. To name a few, I play a character called Catherine who was a closeted PE teacher under Section 28, and she talks about that experience. We also have two characters called Sarah and Charlotte who were activists fighting against Section 28 – they were actually 2 of the people who staged the famous BBC news invasion and abseiled into the House of Lords when the bill was passed. Then, there’s also LB, a student under Section 28 who underwent conversion therapy in their church. I don’t want to tell you too much about everyone – but they all have amazing stories they very generously shared with us, and their accounts make this production what it is.

What are some of the biggest challenges you faced in creating After the Act?

B: First of all, there was an enormous formal challenge in setting real recorded speech to music. There’s not that many verbatim musicals around, and that there’s a good reason why! Undoubtedly the most famous example, which pioneered the form and proved it was possible, is London Road by Alecky Blythe. It’s a total technical masterpiece. She worked closely with composer, Adam Cork, to create the score based on the intonation and speech rhythms of interviewees. Because we were working from a lot of written transcripts – like parliamentary debates – this approach wouldn’t make sense to us. We were also keen to discover our own unique style.

We instead immersed ourselves in the musical genres of the time. Many of our songs began by combining a particular monologue or scene with a musical reference. We had a lot of fun clashing together unexpected contrasts. For example a Billy Bragg-style protest song using the words of right-wing, homophobic campaigners. Or a Bronski Beat-inspired electronic club banger, comprised of horrific tabloid headlines about the AIDS epidemic.

What can looking back at Section 28 tell us about today?

E: The show looks at how laws like this can come into action, and the effects they leave behind. That feels really important at a time like this when trans rights are being discussed in the way they are by politicians and in the media. The conversations and language that was at play and that were happening about gay and lesbian people in the 1980s are being repeated against trans people now, and we need to be aware of that and how this all works, and where it can lead. I would hope the show encourages us to recognise this pattern, and disrupt it in any ways we can.

What do you hope audiences will take away from After The Act?

B: We try never to be didactic with our shows. We’d never want to tell people exactly what they should take away. But I do really hope that people come away a lot more informed about our history. And also galvanised by the huge wave of protests that rose up against Section 28. I think the story of Section 28 shows us that social progress is never guaranteed.

That, unfortunately, it’s more like a pendulum swinging one way and then the next. It’s a story about how a moment of greater visibility and rights for LGBT people was very swiftly followed by a media backlash and a massive government clampdown. Something that feels all too familiar today.

So I think After the Act is a show that tries to remind us not to be complacent. That our hard fought-for rights are not necessarily as safe as we might like to think. That we have to keep vigilant, keep vocally fighting to hold onto them. And to secure those rights for other marginalised groups… sometimes through the medium of song!